The future is now

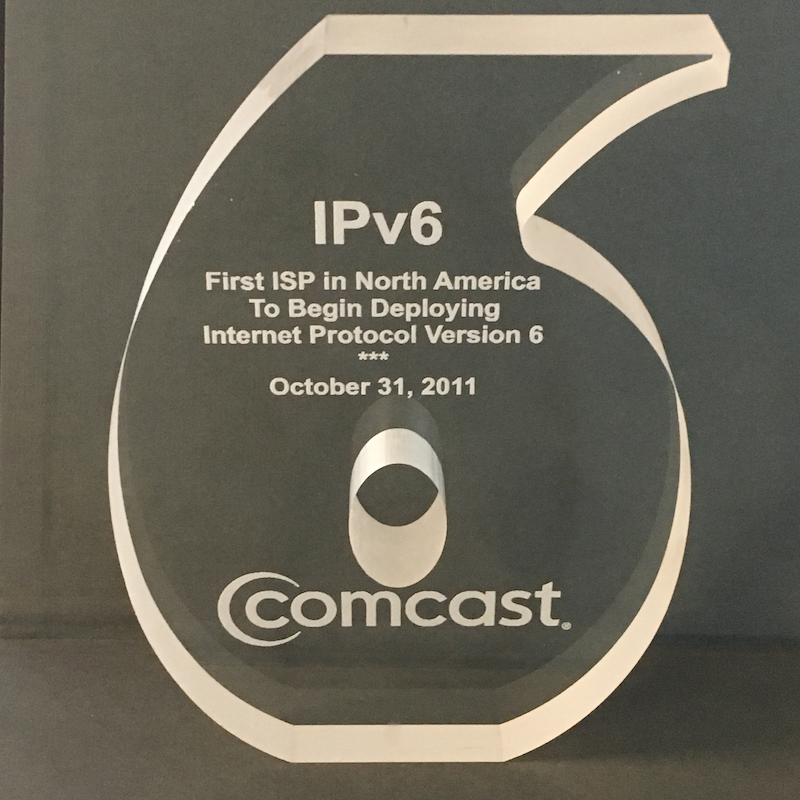

A few years back, Comcast really ramped up its IPv6 deployment for Xfinity Internet, and for good reason, as IPv4 addresses are exhausted at this point. As an engineer at Comcast, I got to play a peripheral role in some of these deployment activities, such as helping to ensure that many of our customer-facing websites were dual-stack IPv6-capable for World IPv6 Launch Day; however, I had virtually no involvement in any of the customer premise IPv6 work. Also, given the fact that my CPE gateway (which happened to be a CheckPoint firewall at the time) was not IPv6-aware anyway, the IPv6 party sort of passed me by.

Fast-forward to 2017 and I finally decided to replace my old, long-out-of-support firewall with something more modern, and at the same time wanted to finally get dual-stack (IPv4 and) IPv6 running on my home network. After a bit of research, I landed on the FortiGate firewall/gateway from Fortinet, as they seemed to pack in quite a few bang-for-the-buck features, not the least of which was pretty good IPv6 support, which for quite a while was a difficult feature to even find in SOHO-class firewalls.

Up to this point, I will admit that my experience with IPv6 was relatively superficial and mostly based on some reading that I had done a decade or so ago. Needless to say, I’ve learned a thing or two as of late, and I’ve decided to document it here because while I’ve found bits and pieces of info and hints to info about some of these topics scattered around the Internet, I couldn’t really find a one-stop-shop that provided all the info I needed to make this work. Also, there were some gaps that I had to fill in myself that I haven’t found elsewhere. Lastly, I don’t do this sort of networking stuff that often, and if I didn’t write it down, I was sure to forget it.

Hopefully, others can benefit from my pain.

The promise of IPv6

One of the most fantabulous features of IPv6 is the notion that clients are configured automatically, generally using SLAAC . This means that things like static addressing, stateful DHCP servers, NAT’ing of (IPv4) RFC 1918 private addresses, etc are all unnecessary. You plug in an IPv6-capable device to a network with an IPv6 gateway, and a bunch of hand-wavy magic occurs that you generally don’t have to care about, other than the fact that it just sort of works and you are now riding the IPv6 rails.

Unfortuantely…

I tend to be a glutton for punishment

Occasionally, I’ve been known to make things difficult for myself. Moreso than they need to be, at least. It turns out that one of these instances happens to be the home network that I maintain. Most folks are content to hook up their gateway (such as one of the residential gateways from Xfinity, or routers from Linksys, Asus, etc, etc) connect their computers and other wireless devices, and carry on with life. This is essentially a fan type network - 1 gateway, bunch of devices connected behind it.

(Un)fortunately, I don’t have that. My main gateway has multiple separate networks behind it, some flat and some not-so-flat - a tree type network. This means that I have yet another router behind the primary gateway.

The upshot of this is that what I envisioned to be a relatively seamless transition to IPv6… was not. At all.

Next Page -> Example Fan Network